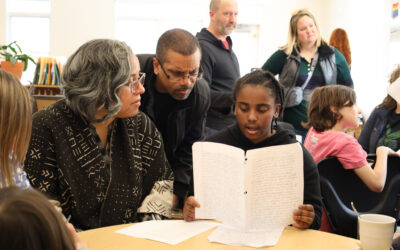

A group of Lower Elementary students share their work with their classmates.

A group of Lower Elementary students share their work with their classmates.

Montessori Mastery: A Learning Process for Life

Students are best motivated to learn when they work on something of their own choosing, at their own pace, and until they determine that they know. But is this realistic in the classroom setting? Can we really expect students to know what they want to pursue, stick with it, and then demonstrate mastery?

Many of us who grew up with a conventional school education had a very different experience: the teacher would enter the classroom with the day’s lessons all planned to be delivered in defined blocks of time within the boundaries of the regular school day hours. The next day was more of the same. Everyone would receive the same lessons at the same time, regardless of interest, readiness, or need for practice to solidify newly presented material. Content was presented in a prescribed curriculum administered by adults. Various quizzes and tests were given within a specified time period to determine whether or not newly presented material was understood. Regardless of the test results, the curriculum moved forward.

One major problem with this approach is that it does not take into account the students. Not all students are interested in the same thing at the same time, nor are they always ready for the same work because they are in the same class. There is a growing body of research that confirms the significant role that choice plays in student motivation and learning. Sue Grossman Ph.D. states strongly in her article, “Offering Children Choices: Encouraging Autonomy and Learning While Minimizing Conflicts,” that, “giving children choices throughout the day is beneficial, even crucial to their development.”

So, how do we change the system?

Montessori is intentionally and appreciably different than conventional models of education. Montessori is a developmentally based approach, in which choice has always been a critical element in our work with students. We cannot force a student to learn. We can create an environment, rich with resources and hands-on materials, that encourages autonomy and independence. We can offer lessons, observe students, and work with them to ensure their progress. We can model, demonstrate, establish and maintain high expectations for engagement and accountability. Ultimately, it is the students who takes ownership of and responsibility for their own learning.

In the words of Dr. Maria Montessori, “Education is a natural process carried out by the human individual, and is acquired not by listening to words, but by experiences in the environment.”

Guiding a class of curious young students, each of whom is making individual choices about what he or she is working on, is no easy feat! How do we support individual interests and pursuits while also ensuring that skills are practiced and expectations for high quality, polished work permeate? We have at our disposal a deep understanding of the developmental needs of the students, uninterrupted work periods where we are available to provide lessons, observe practice, meet with individuals, and offer an abundance of beautiful, engaging materials with which to engage students.

Breaking down the process

A key technique we utilize to present information to students is called the three period lesson. Regardless of the content being introduced, this framework supports on-going work for individuals and groups of students as they move from observation to active manipulation and application, and finally to deep understanding and mastery.

Ms. Shweta gives a lesson to a Children’s House student on a short bead chain.

Ms. Shweta gives a lesson to a Children’s House student on a short bead chain.

The first period: An introduction

During the first period, the Guide presents a new skill, idea, or story to a student. Depending on the developmental needs of the student this presentation may be short and precise: “This is blue.” It may be a naming period where vocabulary is introduced. For older students the first period may be the sharing of an impressionistic story such as The Story of the Universe, where just enough information is conveyed to inspire wonder and awe, and the story itself becomes the springboard for further exploration. This first period is presented in such a way that the students leave curious, excited, and motivated to engage with the work.

A Toddler works independently, exploring types of insects—an example of the second period of the lesson.

Second period: Thorough investigation

The length of time a student spends manipulating, exploring, questioning, and repeating newly presented lessons is not determined by the Guide, but rather by the interest and drive of the student. This period of deep engagement is known as the second period of the lesson. It is the longest and most important part of any lesson. Students are not rushed to complete a task or to prove they have mastered a new skill. Instead, students are encouraged to become thoroughly immersed in their work. For younger students, this usually involves repetition until new skills and concepts are internalized. A student may sort, match, name, and paint with all shades of “blue.” Older students may choose to explore the three states of matter, gravity, the composition of the earth, or formation of mountains after hearing The Story of the Universe. When students freely choose topics that interest them, motivation comes from within and kindles their natural desire to learn. They are learning for learning’s sake, and their drive is ignited.

Curiosity begins with questions and is fed by on-going investigation, discovery, and the sharing of ideas. As older students dive into self-chosen research topics, they rarely work in isolation. Learning is infectious! Students not only enjoy sharing what they are learning, but also invite critical feedback from their peers as they bring their research to completion. Learning to give and receive feedback supports whole-class collaboration. Students encourage one another by giving descriptive feedback that is kind, specific, and helpful. Engaging in the critique process often inspires multiple revisions, encourages further opportunities for developing listening and speaking skills, builds student confidence, and leads to amazing polished work. There are no limits when students share, exchange ideas, and support each other. Expectations for deep engagement and high quality product are modeled and reinforced by peers with the overarching goal being the creation of beautiful work.

Two Adolescent students teach a group of Children’s House students how food scraps are used to make compost.

Two Adolescent students teach a group of Children’s House students how food scraps are used to make compost.

Third Period: Demonstration of Knowledge

So, how do we know when the students know? Third period activity is unmistakable with young students. They show us they know by spontaneously teaching their peers! Newly acquired skills are applied directly in daily activity, whether it is to identify the color blue or by helping a classmate put on her jacket. For older students the third period is manifest in myriad ways. Students know when they are ready to present their work. They have spent time revising and practicing, speaking clearly, making eye contact, fielding questions from an audience, and graciously receiving feedback. They have become “experts” in their topic. Presentations may include a skit, a song or poem, a video, or a model built to scale.

The final facet of the third period for older students is reflection. Students analyze the learning process from start to finish: “What went well?” “What were the challenges and how did I learn from them?” “What would I do differently next time?” Self-reflection inspires ownership of learning. Students are accountable to themselves. They not only begin to understand themselves as learners, but also how to tackle obstacles, work with others, accept feedback, and build the muscle they need to continue learning. John Dewey went as far as to say that “We do not learn from experience…we learn from reflecting on experience.”

Two Children’s House students explore the different types of leaf shapes, veins, and margins.

Two Children’s House students explore the different types of leaf shapes, veins, and margins.

At Greenspring Montessori, students are encouraged to dive into their work wholeheartedly—to make mistakes, and to learn from them. “That’s how learning in a Montessori classroom works – not by memorization, or simply listening to a teacher at the front of a classroom, but by doing.” (threetree.org)

Yes, we do expect students to know what they want to pursue, stick with it, and then demonstrate mastery. They demonstrate this every day, with gusto and an insatiable appetite for more!